Anatomy of Chinese Furniture

How to Tell if a Chair is Authentic, Look at the Arm and Handgrip

By Lark E. Mason, Jr.

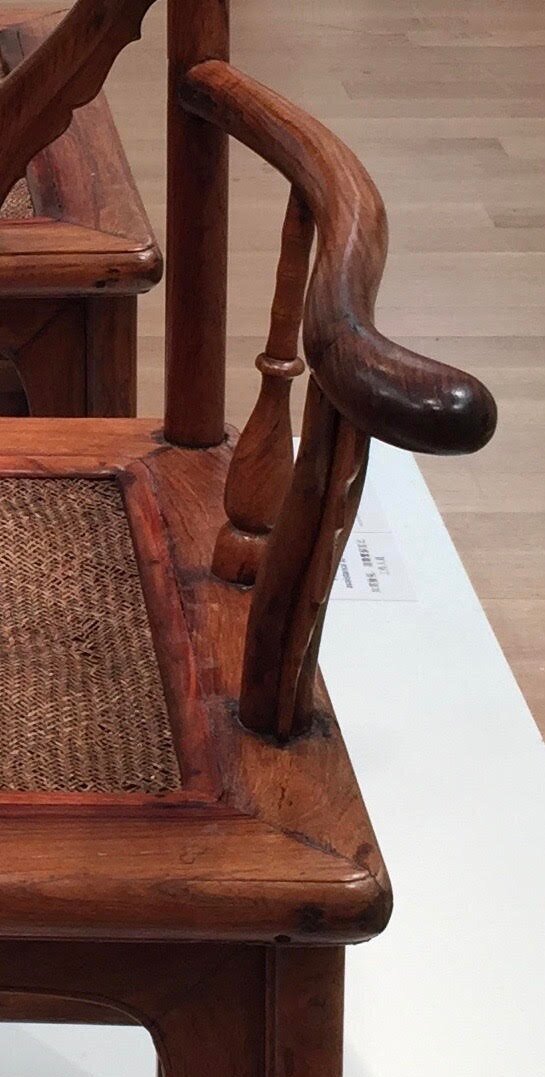

Most people become enthused about Chinese furniture because of the beauty of the wood and the elegant forms, which are superbly engineered with a spare essentialist approach to construction. A form is the sum of its parts, and this ‘part’ is the handgrip of a Chinese Huanghuali Yokeback Armchair of the late Ming or early Qing period. We can only guess what the furniture looked like as it left the workshop. Hundreds of years have passed and during that time the original surface has changed. Light, heat, water, stress, and daily use and wear cause change. These changes are recorded in many ways, but often in barely visible clues that individually or together explain the past of the object.

Arms as in other elements were not turned nor steamed into shapes, but carved from blocks of wood, removing excess material to create the shape for the form. The advantage of this approach is strength. The grain extends forward as seen in this handgrip which gently tapers from the join at the rear leg as it becomes the stile up to the end of the front leg that extends through the seat frame to join the arm. The girth of the handgrip slightly widens and swells into a rounded, curved knob that is comfortably gripped. The stress put upon this handgrip necessitated the increase in dimension. Any sitter would have risen from the seat by pushing down at the join of the front leg to the handgrip, exerting terrific pressure which would have been diffused through the handgrip into the vertical support and down into the seat frame with the adjoining members.

Chairs are moved from one spot to another. Floors are cleaned, rooms emptied and filled. Households move. Gatherings take place. When furniture moves it subtly changes. Whether dragged by the crest rail across the floor, lifted by the arms, or stacked on a cart, pressure and tension flows through the wood affecting the connected joins, and some of these eventually fail. Sometimes innate flaws of nature, a bad spring with not enough water, or a fire, cause the grain to have weaknesses that are unapparent until stress, often repeated stress causes a slight opening eventually resulting in a split. Organic materials decay. We strive to slow decay by conservation, either directly through intervention or indirectly by practical and commonsense handling.

The expectation is that all furniture is undergoing stress from use, have inherent weaknesses that reveal themselves over time, that human misuse and atmospheric changes aggravate and accelerate change, and these and unpredictable occurrences will either eventually wear down the object or will be addressed by intervention to slow down the process. During this process, its possible to see areas that have experienced stresses and predict what may happen if left unaddressed and see what other people before us have done, which may inform us about what we might do.

Woodgrain is not uniform. There are harder aspects and weaker, softer aspects. The lighter colored parts of the grain is the part of the tree that was once new growth, fast growing during the early spring, which gives way to slower growth in the summer months, resulting in dense and harder wood that is darker. This combination of light and dark rings present a distinctive appearance and its not unusual to see narrow, slight cracks following the softer part of the grain. Over time, slight ridges develop between the hard summer growth and the faster, softer spring growth. These can be seen in the image of the chair arm. Protective coverings, usually of wax mixed with other softening agents are used to protect the surface, inhibit the exposure to oxygen and changes in humidity and temperature which promotes decay.

Repeated pressures on the arm are causing the stress fractures. The cabinetmaker was aware that there would be stress at the join of the arm and the front leg, and to ameliorate the damage, joined the arm to the leg with a bamboo peg where the arm is inserted into a mortise cut into the area just below the handgrip, where the tenon at the end of the upper leg is inserted. The larger size of the grip is for added strength at the join where the material was cut away, and for comfort for the sitter. The gouge at the top is from dry rot, likely caused as a result of a metal band, most likely baitong, which is literally ‘white brass’ that wrapped about the join and was attached with small metal pins. Its possible water accumulated here or dampness from the metal ’sweating’ and that repeated wet, dry exchange eventually leached out the oil in the wood and produced ‘dry rot.’ The blackened holes on the upper part of the front leg show where pins were inserted and the acidic reaction of the metal against the wood resulted in the ‘burned’ appearance, and this area may well have had some moisture accumulation. The shadow of the band is clearly seen on the arm but not very clear on the upper part of the leg. These metal bands were commonly used to strengthen the joins and almost all of these decayed and were eventually removed. Repeated contact with human skin and the acids in the oils of the skin caused deterioration, in addition to the stresses at the join and the eventual failure of the pins securing the metal band. The lack of a shadow for the band probably indicates that the wood has been abraded, likely with sandpaper, removing the outer layer of material, and also indicating that the chair was taken completely apart, joins cleaned and repaired and glued and then put back together.

https://collections.artsmia.org/art/4876/yokeback-armchair-china

From a construction standpoint, the cabinetmaker took the steps expected of a skilled craftsman. The point of contact with a person rising and sitting repeatedly was bound to need reinforcement, and that this chair is still useable today after four hundred years of use, is proof of excellent design, craftsmanship, and material. From a conservation perspective, the protective metal band has been removed, but the loss of extra protection is not likely to result in damage, because the chair is today much more highly prized and probably much less used than at the time it was created. Regular use should not be a problem as long as care is taken to address issues such as the gouge in the top and make sure that the surface is waxed and the chair is kept out of areas of extreme changes in heat or cold and humidity.

From a standpoint of authenticity, these small indicators are important. These show slow change and care. These can be mimicked and old wood can be reused to create ’new forms’ that can deceive, but with practice these small, incremental changes can be detected and provide proof with the expectation that similar changes will be apparent on the other elements of the form, appropriate to the amount of stress and wear that those receive.